Even before the release of Football Manager 2024, there was a lot of discourse about the new match engine and how it would enable positional play. It has allowed for formations within a tactic to now vary greatly from when a team is in possession to when it is out of possession (or OOP for short).

Football Manager blogger ‘icon’ FM Grasshopper was one of, if not the first, out of the blocks on this. He explained his take on a 4-1-4-1 tactic OOP, which evolved into a 3-2-4-1 when in possession with CF Monterrey. I highly encourage you to go and read it if you haven’t already, along with his Superclub Diaries save.

The intention of my post below is to explain the formation that I’m currently using with my Bayer 04 side. In it, I’ll go through how I arrived at this formation, and then explain the theory behind it, including how it utilises the new positional play capabilities, before going into look at how it plays out within the match engine.

Origins

The tactic I’ve created originates from a standard 4231, in which I wasn’t really utilising the full capabilities of the new tactical set-ups and match engine. This was in part because I’ve ported this save over from Football Manager 2023 into the new version, and also my preference towards a relatively standard, now somewhat old-fashioned tactic. Over time, I’ve played around with different tactical set-ups as my squad has both the talent and the flexibility to play a range of positions and roles.

Additional to the tactic I’m setting out before, I’ve also come up with a Klopp-inspired tactic, which I may well blog about at a later date. The tactic I’m choosing to write about here is different to that of any real-life football manager that I have watched. This is not to say that this is original, nor am I even sure that real-life teams would want to try this, as I suspect it would be easy to counter in reality. However, it does play some really nice, dominant, aggressive football.

The Theory

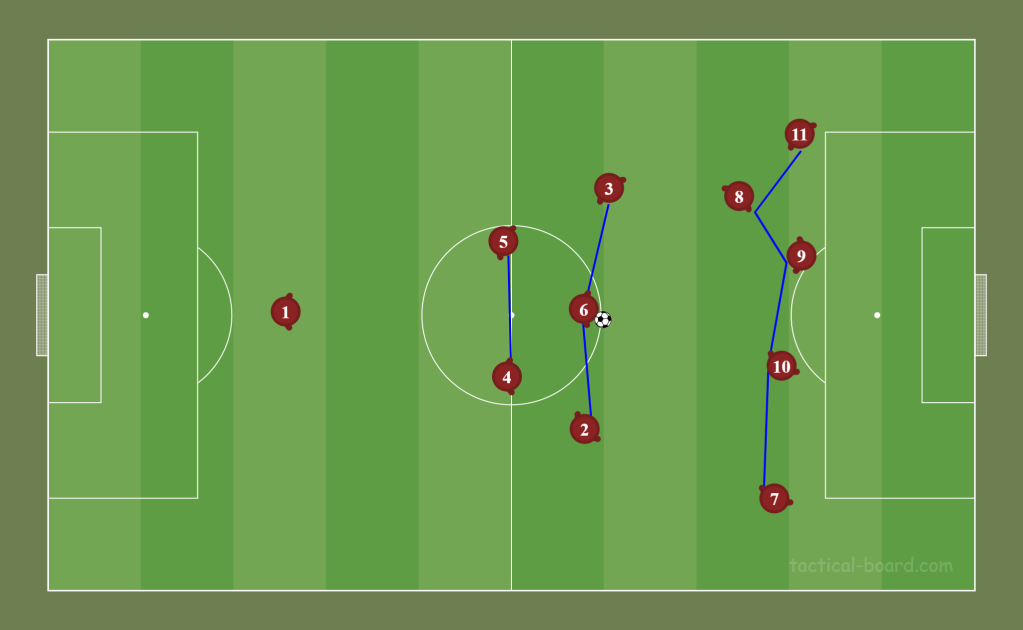

As I already stated, the base of the tactic starts with the archetypal 4231 (see clickable images below), with a higher defensive line selected, along with a high press, and pressing triggers set to be much more often. Your fairly standard gegenpress one might think. Whilst to a point you’d be right, given the player roles and duties that are selected does enable the high press, all action football OOP, but it’s when the team is in possession that it looks very different.

Player positions and roles

Defenders

Starting at the back, the defensive triangle of sweeper ‘keeper and two ball-playing defenders is nothing out of the ordinary for a world-class side that I’ve established at Bayer 04 Leverkusen. What is different is the use of two inverted wing backs. Famously, Guardiola, Klopp and Arteta have been inverting full backs into midfield for a while now, although Guardiola has more of a preference for a libero in John Stones. In this inverted set-up, the other full back will typically slot into a central defensive area to make a back three in a 3-2 shape.

Instead, I’ve opted for a 2-3 shape, leaving the two central defenders as the last line of defence. I’ve also opted to stagger the line of three by having one of the two inverted wingbacks be slightly more aggressive in the support duty. This enables different passing options, and avoids a flat straight pass from the central pivot, which is the deep-lying playmaker (on support duty), which could be taken advantage of through an opposition press and interception.

As can be seen in the image below, when the team move up the field in possession of the ball, this back four, with two central midfielders in front of them now change to the 2-3 shape, with the right-sided deep-lying playmaker drawing in to the centre to act as a fulcrum. Through him, the play can be dictated, with his central positioning allowing him access to the full range of the field given his passing skill and ability. Yet, should he need to make an easier, less risky pass, he can do so to the two inverted wingbacks either side of him. This provides choices and means that we can be dominant in possession, without being concerned about having possession for possessions sake, especially given the forward options.

Attackers

This leads me nicely to the ‘front five’, which originally was only a four. The mezzala will move swiftly up field and overload the left half space with the inside forward on that flank. Consequently, it provides problems for the right-side of any defensive system due to the need to mark two players for a right full/wingback, or for a defensive system to pull back the right-sided winger. This can, depending upon the opposition’s own tactical set up, give the left-sided inverted wingback for my side more time and space on the ball to act as something of a play-maker himself, causing havoc with some of his deep balls into space in behind the opposition, as we will see with an example later.

The complete forward is also a key to this. If we are in possession and we’re looking to play through the middle, rather than just staying nailed to the front line, he will drop into receive balls into feet. The player trait ‘comes deep to get the ball’, which my complete forward, Priso, has is a positive because it can move defenders out of possession off their line, creating a pocket for others to run into, which in turn further drags the opponents back line out of its structure if they’re opting to man mark. Priso’s movement can also be lateral along the final defensive line of the opposition. As we see in the above graphic, if he were to move across towards the left channel, this would allow the attacking midfielder (on attack duty) to join him as a central attacker.

The inverted winger on the right will remain wide in initial build up, but then look to cut in laterally (horizontal to the 18-yard box almost) and look for passing options for a killer ball, or to take on a shot. With four willing runners or space creators to his left, he’s not short of options for either the pass or a shot.

By having a front five, this allows a myriad of triangles to form, most of which run through the central pivot of the deep-lying playmaker. The below graphic shows just how many interchanges could be played via the ‘six’ in this formation when in possession. He has a considerable choice of passes he could make to enable an assist, or, perhaps more likely, a pre-assist.

In Possession – the match engine reality

In the match engine, when the team is in possession, this plays out in a broadly similar fashion to the theoretical explanation above. The attacking midfielder has a close relationship with the centre forward, the two wingbacks have inverted, and the mezzala has gone on ahead, moving on from his fellow deep-lying central midfielder, who has sat narrower than his place within the OOP tactic screen might have suggested.

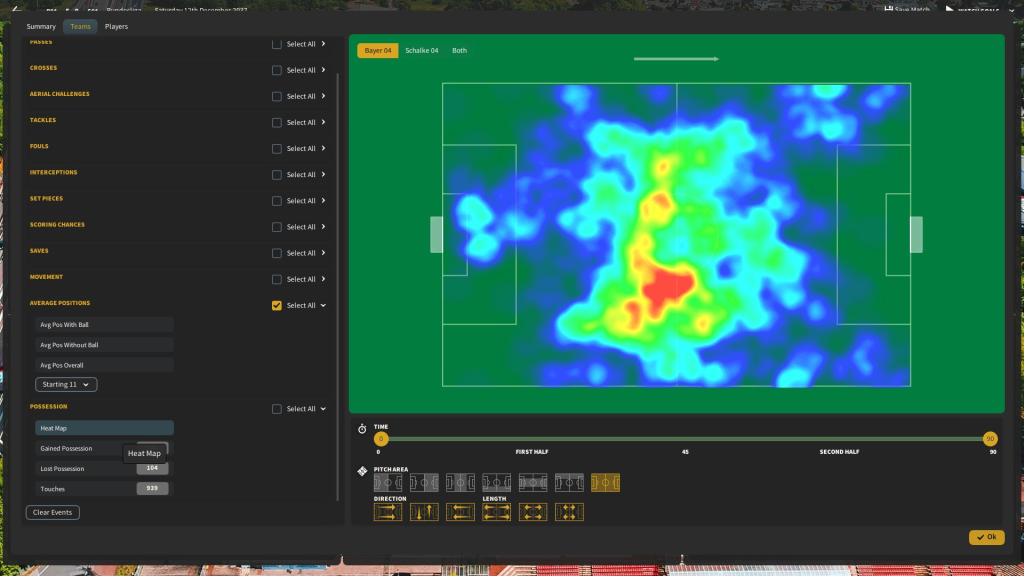

When it comes to possession, you can see from the heat map where the ball was most commonly – and how it’s circulating to the deep-lying playmaker in the six position more often than any other area. This also demonstrates the desire to work the ball around before we enter the box, and just how frequently we were on the ball across the central areas of the pitch. There is plenty of scope to move the ball around with the movement of our players to attempt to manipulate or lull the opponent into a mistake.

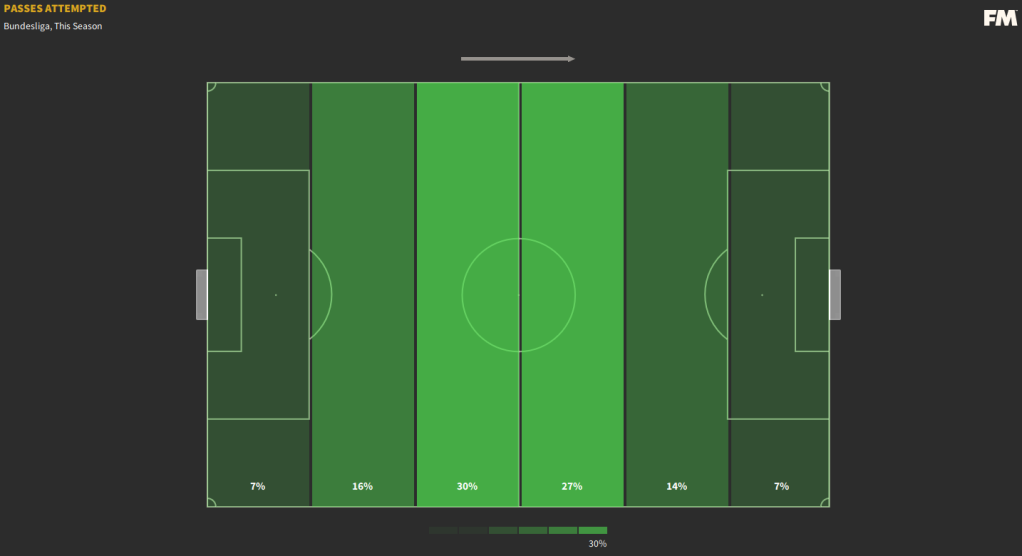

Here, you can see the percentage frequency of passes across the depth of the pitch. We are clearly prepared to play the ball around in the centre of the midfield, which fits with our work ball into the box approach. The fact that the three in the back five are so close together makes it easy to recycle possession, and there is almost always a pass back to one of the ball playing defenders behind them, as invariably the opposition don’t look to press the back two.

What’s also important to see is the compactness, not so much laterally, but vertically. When in possession, passes can be short and sharp to drag opponents out of position, or play can be more considered, with the safe option always available due to the proximity of a teammate. Here, the in-possession image below of the average positions of the players, shows just how compact it can be. The average distance between the defensive and attacking lines against Benfica is tightly compressed. The beauty of this is that if a passing lane is opened up by a movement of a third player’s ghost run, then that can allow a far shorter progressive pass through the opposition’s midfield lines and straight into the attacking third. This can minimise risk, but maximise reward – we’re likely to maintain possession, but also cut through the oppositions defensive lines quickly, provided the off the ball movement of our own players is effective.

The number of progressive passes enabled by this formation and subsequent changes to the shape through the positional play can be evidenced by Fornal’s metrics – our ‘Juan in the box’.

As you can see from the pizza chart that comes with the MustermannFM skin, he has not only has the ability, but also the options with forward runners to make these types of passes. He acts as a quarterback between the two ‘wide’ defenders. He’s in the ninetieth percentile of all deep-lying playmakers across the top twenty leagues.

This snapshot of the passes he’s received from his teammates in an away game against Rennes in the Champions League semi-final highlight his structural importance. He received 72 passes in total, but I’m only showing those that he received in the central third to remove receiving the ball from throw-ins. You really get a feel for how much he is sought out, and the shortness of those passes that gave gone into him.

His central positioning allows him to take the ball in, and then look for a teammate in a more advanced position, or move the ball to either side to pull the opposition defence out of its shape, as indicated by the graphic below. The pass in yellow was a key pass into Batuhan Kılıç who scored low into the bottom left corner (typically, FM didn’t have this as a pass assist, even though it was).

To demonstrate the effectiveness of this tactical approach within the centre of the pitch during build up, the rotation option, Anténor Aristide, shows very similar numbers, if marginally better progressive passes and more passes completed, though is less active defensively. It’s worth pointing out though, that given these are play-making midfielders, the lack of defensive actions isn’t entirely surprising given that they’re being compared directly against more defensively aggressive ball-winning midfielders.

However, it isn’t just the deep-lying playmaker that can deliver the progressive passing. The inverted wingbacks can also deliver a large number of forward passes into the opposition half. Nyamsi, Elliot and Ballesté have all recorded a high frequency of progressive passes into attacking areas of the pitch over the course of the season, which has helped our attacking build-up play.

The following phase of play is a great illustration of this. In the initial instance, Berends (right-sided IWB) has played a square pass across to Ballesté, who has the left-hand side open to him to play a pass forwards thanks to Schalke’s narrow 5122 formation.

Bachev realises the space behind him, and drops off the forward line where he’d initially created an overload with Batuhan Kılıç. This shorter pass has the effect of dragging out a Schalke defender with Bachev, and as their defensive line has started to drop to guard for the ball over the top into Parilla, Restelli has effectively remained stationary, and as a result is now unmarked for Bachev to pass into him.

The left-sided centre back for Schalke has no choice but to engage with Restelli by closing him down, but the clever off-the-ball run by Parilla to his right (our left) opens up a passing lane for Restelli to lay the ball in for Batuhan Kılıç between the central and right-sided centre backs.

This results in Batuhan Kılıç having a clean run through on goal, culminating in a good finish outside of the goalkeeper’s reach as it nestled in the back of the net. A quick attack, which is direct and involves clever off-the-ball movement to pull the defence out of their set-up. Just look at how the back five of Schalke’s ends up – a complete mess, with no-one really marking anybody.

In another example of build-up that led to a goal, you can see in the below graphic that our centre back Schepers has the ball, and a very clear 2-3 in our set-up, a slightly staggered front five, with those players wide across the pitch, and a clear attempt to overload down the left half-space with Engibarov playing the mezzala role.

Schepers plays the easy, short pass into Ballesté, who is facing Schepers. Engibarov makes his move to drop closer to Ballesté to receive a short pass too, but Weuthen starts to make a run off-the-ball in behind the high defensive line that Mainz have opted for.

Ballesté spots this movement, and clips a ball over the top of the defence for Weuthen to run onto, spring the offside trap with the progressive pass.

Given Weuthen’s pace, the opposition defenders aren’t able to catch him, and he’s through on goal to score our second goal of the game and put us 2-1 up. We’ve gone from being really vertically compact initially in possession, using this to our advantage to play over Mainz’s high line from our inverted wingback, and utilise the pace that we have in the side to create a gilt-edged opportunity for one of our front five.

Out of possession (OOP) – the match engine ‘reality’

Yet, for all the benefits a compact build-up allows for, it is for defensive reasons that the compactness is important. The high line of engagement had to be matched with the higher defensive line. If the team were to sit back and regroup when possession was lost, then there would be huge pockets of space for the opponents to take advantage, in particular down our flanks. Equally, if there was a low defensive line, there would be huge gaps for our opponents to play through our lives and counter quickly against a defensive line that was trying to quickly reorganise itself whilst under pressure.

As it is, should the ball be turned over, there will be up to three teammates all able to close in on the opposition player to try and turn the ball back over. The front five can rush an opponent given the right trigger press, or look to drop back and look to hit back at a team looking to build up with their defensive players.

Should there be a quick turnover with the front five, we’re relatively safe because we have the ‘back five’ players who are not directly engaged in the attack, i.e. these five represent our ‘rest defence‘.

The below graphic against Benfica away in the Champions League demonstrates this rest defence perfectly. You can see the three (Portilha, Aristide and Schepers) and two (Berends and Wozniak) at the back as we look to move forward on a quick counterattack.

Whilst this shows us in the attacking phase, the rest defence is designed to prevent us from conceding goals. The image shows just how narrow the 442 of Benfica are, and also that their two strikers are completely covered by the inverted wingbacks and the deep-lying midfielder. If there was to be a turnover against us, it’s probable that any ball into them will see either an interception or an easy tackle by a two-v-one in our favour. This is what Gaël Clichy and Jamie Carragher were talking about on Monday Night Football – that the inverted wingbacks (they called them fullbacks) are actually there not just to help progress the ball forwards, and pull the opposition out of their defensive shape, but to be ready to defend against counterattacks. Our three are ready to defend as the front line in a transition phase. Given we have the man advantage, one of these defenders can engage in closing an opponent down, and pass on the defensive duties to a teammate, safe in the knowledge that they are still guarded.

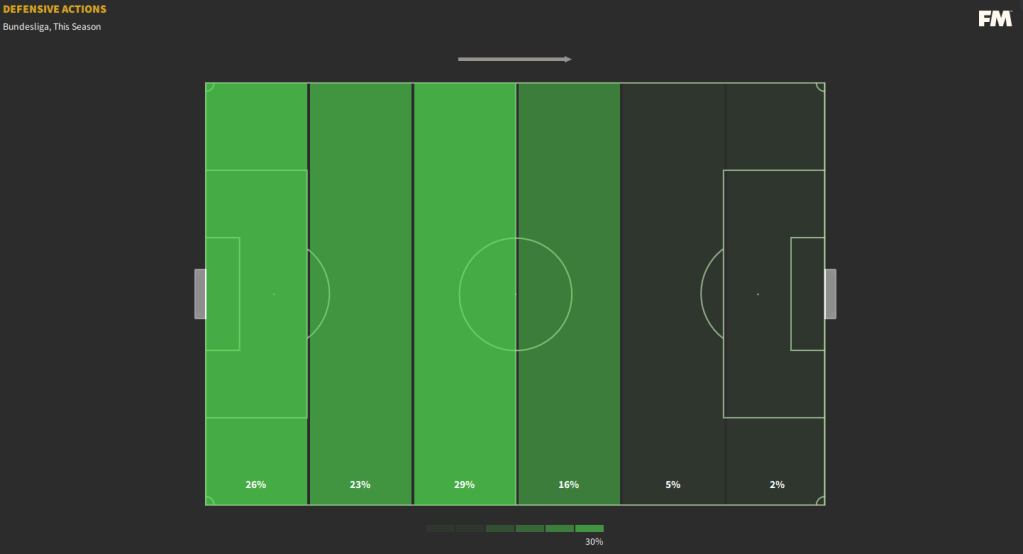

Below is the in-game graphic for our possession regains, and you can easily see just how good we are at stopping teams from reaching our defensive third by cutting them off before they’re able to progress the ball into that space. This helps to minimise opposition shots, and enables us to then either quickly counter or look to recycle possession.

The selection of ‘trap inside’ within the tactic on the ‘out of possession’ tab is also playing its part here. Given we have a narrow defensive set up in the first phase of a turnover, shown again in the screengrab of the moment against Benfica, it makes sense to try to quickly funnel the opponents into this trap of three relatively narrow defenders, to enable interceptions and tackles to be made. Out wide, we could be outnumbered by wingers and full/wingbacks, whereas in the centre, it’s far more likely that we would have the superior numbers.

This time, the graphic shows our defensive actions. Whilst we seek to gegenpress, we’re far more effective at it deeper towards our own goal. Yet, it’s still the case that we’re very active in the defensive half of the central third of the field.

Statistical Analysis

So how does this stack up statistically? Given the side that I’ve established at Bayer 04 over the last fourteen and a bit years, we’re incredibly dominant to the point where we only lost three games across all competitions, winning all the trophies that were available to us. Therefore, if you are going to adopt this tactic, you should be aware of the strength of this side across all facets.

Nonetheless, here you can see just how dominant we are – first across a range of metrics that you would want to be first in if you’re going to win the league.

When comparing the base level attacking (npxG) against defensive metrics (xGA), you can see that we’re separated from the pack by some considerable distance. If we compare ourselves against Bayern Munich, then they had 1.64 xG to our 2.61, and 0.74 xGA90 versus our 0.65. Now all this is well and good – it says we’re good in attack and good in defence, but it never explains why.

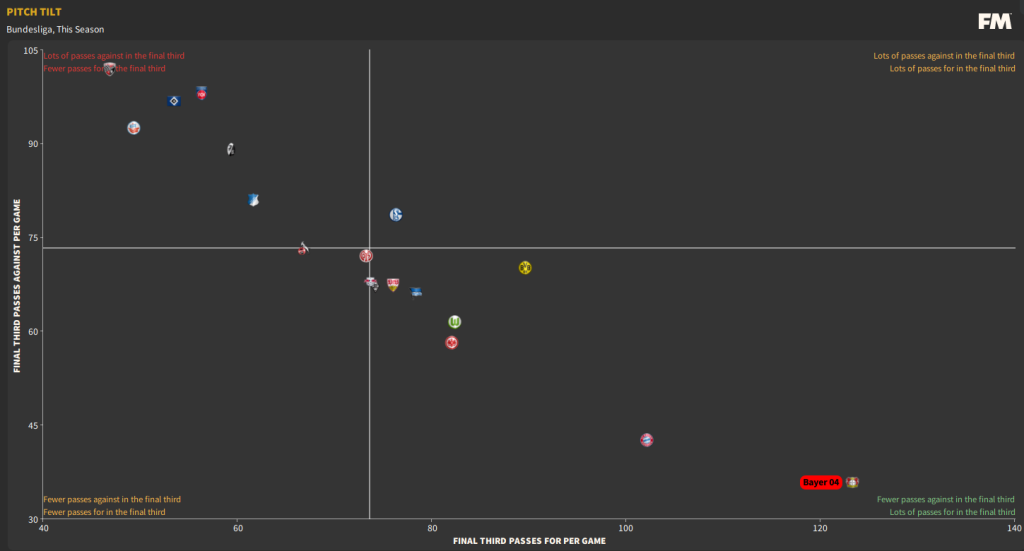

This next infographic helps start to explain the story. Here is the ‘pitch tilt’ for the Bundesliga over the 2037-38 season, clearly shown that we have by far and away the fewest passes against us in our defensive third per game at around 34 passes, but make in excess of 123 each match against out opponents in their defensive third. Once we’re in the opponents third, we’re good at keeping it, and working it around, and that we don’t let them do the same – maximising our goal threat, and minimising the opponents. So far so good, but we’re still a way away from being able to say what helps us to achieve this.

To help explain the lack of opponents passes in our defensive third, we can look at the efficiencies of our defensive line against the number of opposition passes per defensive action (OPPDA for short). Here, we’ve by far and away the highest defensive line. With a quick back four, we’re able to take advantage of this and press up the field as a coherent team, without having to worry about a slow defender being caught out by a ball over the top. This higher defensive line means that we can then more effectively engage in the press, and help win the ball back higher up the field than we would do had we had to retreat back into our own half. Whilst our press could have been more effective, and thus generating a lower OPPDA, we’re not far off the league average for allowing the opponents little time and space with which to start to play around of transitional and defensive shape.

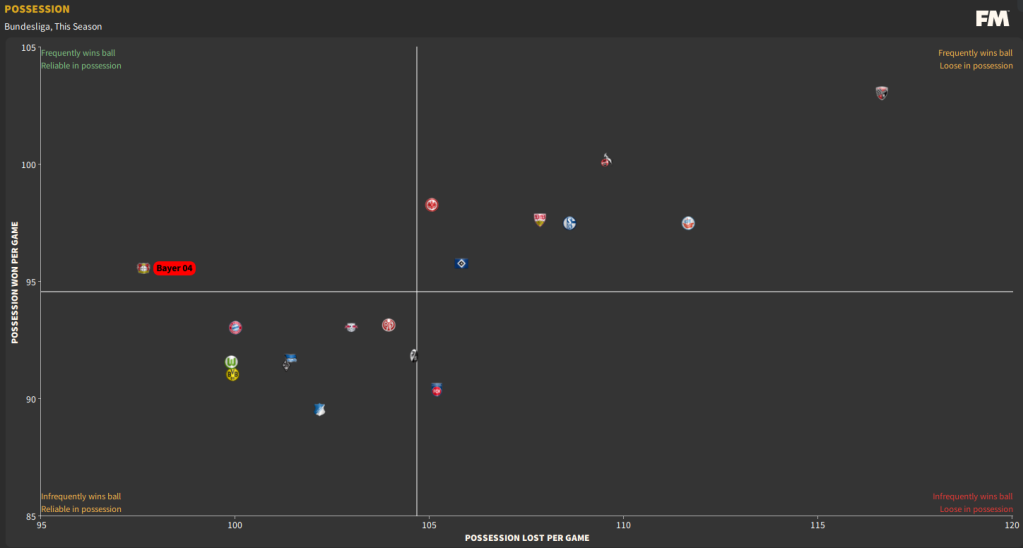

This final graph from the data hub indicates that we very infrequently give the ball away, and win it back more than the average. Our compressed shape and willingness to counter press indicates that we’re winning the ball back and then good at keeping it away from our opponents.

I’ve purposefully refrained from providing our defensive metrics from the data hub, largely because they can be very misleading. We barely tackle with only twenty attempts per game, but are efficient when we do, with a 77% success. We also make very few clearances and blocks – which shouldn’t be surprising given that the opposition don’t get into our defensive third very much to make a shot, and given that we’d look to play out of defence should we win the ball back. Yet, we are sixth best for interceptions – with 10.83 per 90, helping us to win the ball back some 95.56 times per game (8th best), and I think this says a lot given we have 59% possession on average across the season. It’s our front foot approach to winning the ball back, which then forces the opposition into forcing a pass whilst we read the game and place ourselves into their passing lanes.

If you want to download the tactic, you can do so here on Steam, or here on MediaFire. Then simply move it into your Football Manager folder marked “tactics”, head into the game and go to the Tactics screen and then the drop down menu above the tactic itself and select “Load” then select the tactic and you’re away.

If you try the tactic out, then let me know how you get on in the comments section below.